Back

(131) Self-Directed Ketamine Therapy and Withdrawal Syndrome: A Case Report

Saturday, April 26, 2025

9:45 AM – 1:15 PM

Location: Aurora Ballroom Pre-Function, Level 2

Zachary J. Brown, D.O.

Hospitalist, Addiction Medicine Fellow

University of Colorado, Colorado

Dale J. Terasaki, MD, MPH

Physician

Denver Health & Hospital Authority, Colorado

Presenter(s)

Non-presenting author(s)

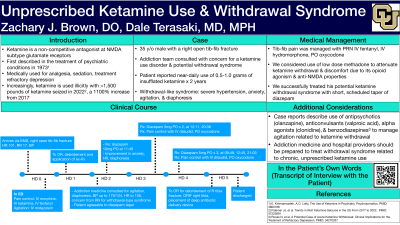

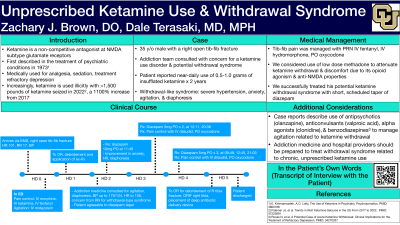

Background & Introduction: Ketamine, a non-competitive antagonist at NMDA subtype glutamate receptors, has multiple established and developing medical uses. It is frequently used in anesthesia and conscious sedation, and was first described in the treatment of psychiatric conditions in 1973 [1], though one of its enantiomers, esketamine, was only approved by the United States FDA for the treatment of depression as recently as 2019 [2]. It is also used illicitly as a recreational drug, with data from the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics showing 1.1 million first-time users of hallucinogens (ketamine included) in 2023. Law enforcement agencies seized more than 1,500 pounds of ketamine in 2022, over 1100% increased from 2017, indicating the supply of illicit ketamine being brought into the U.S. is growing [3]. There is an unknown percentage of the population that utilizes ketamine therapeutically for various conditions such as pain, depression, and anxiety. However, when use becomes chronic and heavy, there may be profound adverse effects. In this report we explore the case of a hospitalized 35-year-old male patient who met DSM-V criteria for a moderate use disorder related to ketamine, including a possible withdrawal syndrome.

Case Description: Mr. E was hospitalized after a scooter accident in which he sustained an open tib-fib fracture and ankle dislocation. Initial vitals on arrival to the ED (after administration of opioid analgesia by EMS) were temperature of 36.7 C, pulse 63 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, blood pressure 155/112, oxygen saturation 96% on room air. His blood pressure increased further to as high as 207/113 on the evening of hospital day 0. The patient was taken for washout and external fixation on hospital day 1.

In the post-op period, the patient was treated only with PRN doses of oral and intravenous opioids. At approximately hour 36 of his hospitalization, the morning of hospital day 2, he developed a constellation of agitation, anxiety, restlessness, diaphoresis, tachycardia, and hypertension, while subjectively reporting his pain to be well-controlled. The patient denied medical history but reported daily use of 0.5-1.0g intranasal ketamine powder, with his last use just before his accident. The patient reported cocaine and alcohol use a few times per month, and marijuana use a few times per week. He denied any intentional use of illicit opioids, and did not believe his ketamine supply to be contaminated with any fentanyl.

The patient’s withdrawal syndrome was successfully treated with a 3-day scheduled taper of diazepam. After clinical stabilization, the patient was able to provide an insightful interview in which he denied severe discomfort during his withdrawal, but did report a subjective decrease in anxiety and irritability after his benzodiazepine taper. He reported that several years ago, he had tried ketamine for the first time in a recreational capacity, and found that it improved his anxiety and, at times, anorexia. Two years ago, he began daily use of ketamine for therapeutic purposes, initially obtaining medical-grade liquid ketamine and baking it down to a powder at home to use via insufflation. As this supply waned, he had only been able to find ketamine powder, which he got from a select few in-person sources, and believed to be uncontaminated. He discussed his rapid increase in tolerance, needing upwards of 6.25mg/kg of ketamine to fulfill daily responsibilities, well beyond typical dissociative dosing. He stated ketamine was starting to impact his interpersonal relationships, and obtaining and using ketamine was taking increasing amounts of his time each day.

Conclusion & Discussion: Though Mr. E’s withdrawal syndrome was successfully treated with benzodiazepines, there was consideration for a component of opioid withdrawal, due to ketamine’s interaction with the opioid system of neurotransmitters [4], but the patient remained comfortable on PRN doses of oxycodone and hydromorphone for post-op pain. We considered utilizing a very small dose of methadone due to its opioid agonism and anti-NMDA properties, but this did not become necessary. Additionally, we considered use of dronabinol, a synthetic THC analogue, in case the patient’s marijuana use was factoring into his withdrawal syndrome. Due to the patient’s hypertension, we considered xylazine withdrawal, if his ketamine supply had been contaminated. The patient was very confident that his supply was untampered, and he had not felt any difference after use recently. Thus, we did not utilize dexmedetomidine or another alpha-2 agonist to treat him.

Patients who engage in self-directed ketamine use may do so with the aim of treating psychiatric and physical symptoms. However, in doing so, they may ultimately meet DSM-V criteria for substance use disorder, though “ketamine use disorder” does not currently exist as a diagnosis. Finally, hospitalized patients who regularly use ketamine can potentially develop a withdrawal syndrome that requires medical management.

References: 1.

E. Khorramzadeh, A.O. Lotfy, The Use of Ketamine in Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, Volume 14, Issue 6, 1973, Pages 344-346, ISSN 0033-3182, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(73)71306-2.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033318273713062)

2.

Torrado Pacheco A, Moghaddam B. Licit use of illicit drugs for treating depression: the pill and the process. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2024;134(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1172/jci180217

3.

Palamar JJ, Wilkinson ST, Carr TH, Rutherford C, Cottler LB. Trends in Illicit Ketamine Seizures in the US From 2017 to 2022. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(7):750-750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.1423

4.

Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, Sudheimer K, Pannu J, Pankow H, Hawkins J, Birnbaum J, Lyons DM, Rodriguez CI, Schatzberg AF. Attenuation of Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine by Opioid Receptor Antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 1;175(12):1205-1215. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020138. Epub 2018 Aug 29. PMID: 30153752; PMCID: PMC6395554.

Case Description: Mr. E was hospitalized after a scooter accident in which he sustained an open tib-fib fracture and ankle dislocation. Initial vitals on arrival to the ED (after administration of opioid analgesia by EMS) were temperature of 36.7 C, pulse 63 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, blood pressure 155/112, oxygen saturation 96% on room air. His blood pressure increased further to as high as 207/113 on the evening of hospital day 0. The patient was taken for washout and external fixation on hospital day 1.

In the post-op period, the patient was treated only with PRN doses of oral and intravenous opioids. At approximately hour 36 of his hospitalization, the morning of hospital day 2, he developed a constellation of agitation, anxiety, restlessness, diaphoresis, tachycardia, and hypertension, while subjectively reporting his pain to be well-controlled. The patient denied medical history but reported daily use of 0.5-1.0g intranasal ketamine powder, with his last use just before his accident. The patient reported cocaine and alcohol use a few times per month, and marijuana use a few times per week. He denied any intentional use of illicit opioids, and did not believe his ketamine supply to be contaminated with any fentanyl.

The patient’s withdrawal syndrome was successfully treated with a 3-day scheduled taper of diazepam. After clinical stabilization, the patient was able to provide an insightful interview in which he denied severe discomfort during his withdrawal, but did report a subjective decrease in anxiety and irritability after his benzodiazepine taper. He reported that several years ago, he had tried ketamine for the first time in a recreational capacity, and found that it improved his anxiety and, at times, anorexia. Two years ago, he began daily use of ketamine for therapeutic purposes, initially obtaining medical-grade liquid ketamine and baking it down to a powder at home to use via insufflation. As this supply waned, he had only been able to find ketamine powder, which he got from a select few in-person sources, and believed to be uncontaminated. He discussed his rapid increase in tolerance, needing upwards of 6.25mg/kg of ketamine to fulfill daily responsibilities, well beyond typical dissociative dosing. He stated ketamine was starting to impact his interpersonal relationships, and obtaining and using ketamine was taking increasing amounts of his time each day.

Conclusion & Discussion: Though Mr. E’s withdrawal syndrome was successfully treated with benzodiazepines, there was consideration for a component of opioid withdrawal, due to ketamine’s interaction with the opioid system of neurotransmitters [4], but the patient remained comfortable on PRN doses of oxycodone and hydromorphone for post-op pain. We considered utilizing a very small dose of methadone due to its opioid agonism and anti-NMDA properties, but this did not become necessary. Additionally, we considered use of dronabinol, a synthetic THC analogue, in case the patient’s marijuana use was factoring into his withdrawal syndrome. Due to the patient’s hypertension, we considered xylazine withdrawal, if his ketamine supply had been contaminated. The patient was very confident that his supply was untampered, and he had not felt any difference after use recently. Thus, we did not utilize dexmedetomidine or another alpha-2 agonist to treat him.

Patients who engage in self-directed ketamine use may do so with the aim of treating psychiatric and physical symptoms. However, in doing so, they may ultimately meet DSM-V criteria for substance use disorder, though “ketamine use disorder” does not currently exist as a diagnosis. Finally, hospitalized patients who regularly use ketamine can potentially develop a withdrawal syndrome that requires medical management.

References: 1.

E. Khorramzadeh, A.O. Lotfy, The Use of Ketamine in Psychiatry, Psychosomatics, Volume 14, Issue 6, 1973, Pages 344-346, ISSN 0033-3182, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(73)71306-2.

(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0033318273713062)

2.

Torrado Pacheco A, Moghaddam B. Licit use of illicit drugs for treating depression: the pill and the process. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2024;134(12). doi:https://doi.org/10.1172/jci180217

3.

Palamar JJ, Wilkinson ST, Carr TH, Rutherford C, Cottler LB. Trends in Illicit Ketamine Seizures in the US From 2017 to 2022. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80(7):750-750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.1423

4.

Williams NR, Heifets BD, Blasey C, Sudheimer K, Pannu J, Pankow H, Hawkins J, Birnbaum J, Lyons DM, Rodriguez CI, Schatzberg AF. Attenuation of Antidepressant Effects of Ketamine by Opioid Receptor Antagonism. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Dec 1;175(12):1205-1215. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020138. Epub 2018 Aug 29. PMID: 30153752; PMCID: PMC6395554.

Learning Objectives:

- Upon completion, the participant will be able to recognize substance use disorder related to ketamine.

- Upon completion, the participant will be able to recognize a withdrawal syndrome related to ketamine.

- Upon completion, the participant will be able to successfully treat or start treating a withdrawal syndrome related to ketamine.