Back

(10) Exploring Street Medicine's Acceptability: A Qualitative Study of Team Member Perspectives

Friday, April 25, 2025

9:45 AM – 1:15 PM

Location: Aurora Ballroom Pre-Function, Level 2

- AH

Ashleigh N. Herrera, PhD, LCSW

Assistant Professor

California State University, Bakersfield, California

Presleigh Beshirs

MSW Student

California State University, Bakersfield, California

Presenter(s)

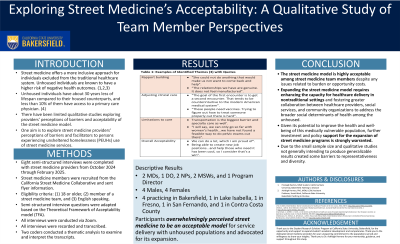

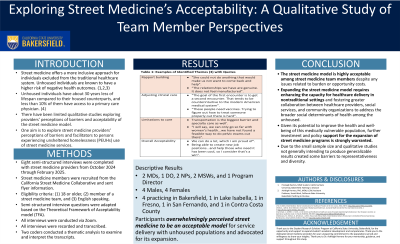

Background & Introduction: Street medicine seeks to address health disparities among persons experiencing unsheltered homelessness (PEUH). Street-level-based healthcare is one intervention to decrease health inequalities within vulnerable populations. These teams typically operate in shelters, streets, and encampments (Tito, 2023), bringing care directly to the individual in their environment. Chronic homelessness comes with a multitude of challenges, including accessing consistent healthcare within a traditional care model (Omerov et al., 2019). Homelessness is a complex issue requiring an adaptive approach when addressing the health needs of unsheltered individuals. While multiple street medicine teams and mobile clinics are operating throughout the United States (Kaufman et al., 2024), minimal qualitative research has been conducted on the street medicine team members’ perceptions of the accessibility and acceptability of this approach. This study aims to describe team members' perceptions of the acceptability of street medicine services compared to traditional healthcare model through the lens of the theoretical framework of acceptability.

Methods: Guided by the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA), one-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted from October 2024 to January 2025 via Zoom with eight professionals who work on street medicine teams across the state of California. Audio files were transcribed verbatim and analyzed via an inductive and deductive thematic approach using a grounded theory approach to discover emerging patterns in the data.

Results: Three major themes emerged: 1) the importance of rapport building strategies with unhoused patients, 2) adapting approaches to clinical care to the realities of the streets, and 3) limitations to offering care through a street medicine model. Participants emphasized the value of consistency, providing basic and harm reduction supplies, and treating unhoused patients with dignity and respect as key engagement and trust-building approaches with a population with significant experiences of discrimination in healthcare settings. Barriers to providing care through the street medicine model included large geographical coverage areas, the transient nature of the unhoused patients, missing key team members to support with case management and behavioral health, lack of housing resources, and difficulty coordinating specialty care. Overall, many of the participants felt comfortable modifying traditional clinical care approaches and accepted the burdens and limitations of the street medicine model to meet their patients "where they are at," improve their social determinants of health, and enhance the health and well-being of this underserved and medically vulnerable population. Participants overwhelmingly perceived street medicine to be an acceptable model for service delivery with unhoused populations and advocated for its expansion.

Conclusion & Discussion: This study highlights both the promise and the challenges of providing healthcare to unhoused populations through the street medicine model. While participants possessed a positive affective attitude about and belief in the ethicality of street medicine services, participants also discussed the obstacles to service provision, including the lack of supportive infrastructure, such as case management, behavioral health services, and access to housing resources. These findings suggest that while street medicine is a valuable approach to addressing the immediate healthcare needs of unhoused individuals, its effectiveness hinges on addressing systemic barriers such as access to housing and comprehensive social support services. As such, expanding the street medicine model requires not only enhancing the capacity for healthcare delivery in nontraditional settings but also fostering greater collaboration between healthcare providers, social services, and community organizations to address the broader social determinants of health among the unhoused population. Given its potential to improve the health and well-being of this medically vulnerable population, further investment and policy support for the expansion of street medicine programs are strongly warranted.

References: Kaufman, R. A., Mallick, M., Louis, J. T., Williams, M., & Oriol, N. (2024). The Role of Street Medicine and Mobile Clinics for Persons Experiencing Homelessness: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 21(6), 760.

National Alliance to End Homelessness. Racial Disparities in Homelessness Persist: A Data Snapshot. https://www.endhomelessness.org/resource/racial-disparities-in-homelessness-persist-a-data-snapshot/. Accessed 10 July 2024.

Omerov, P., Craftman, Å. G., Mattsson, E., & Klarare, A. (2019). Homeless persons’ Experiences of Health‐ and Social care: a Systematic Integrative Review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(1).

Richards, J., & Kuhn, R. (2022). Unsheltered Homelessness and Health: A Literature Review. AJPM focus, 2(1), 100043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focus.2022.100043

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2023). HUD 2023 PIT Count Report. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2023-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

Tito E. (2023). Street Medicine: Barrier Considerations for Healthcare Providers in the U.S. Cureus, 15(5), e38761.

Methods: Guided by the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA), one-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted from October 2024 to January 2025 via Zoom with eight professionals who work on street medicine teams across the state of California. Audio files were transcribed verbatim and analyzed via an inductive and deductive thematic approach using a grounded theory approach to discover emerging patterns in the data.

Results: Three major themes emerged: 1) the importance of rapport building strategies with unhoused patients, 2) adapting approaches to clinical care to the realities of the streets, and 3) limitations to offering care through a street medicine model. Participants emphasized the value of consistency, providing basic and harm reduction supplies, and treating unhoused patients with dignity and respect as key engagement and trust-building approaches with a population with significant experiences of discrimination in healthcare settings. Barriers to providing care through the street medicine model included large geographical coverage areas, the transient nature of the unhoused patients, missing key team members to support with case management and behavioral health, lack of housing resources, and difficulty coordinating specialty care. Overall, many of the participants felt comfortable modifying traditional clinical care approaches and accepted the burdens and limitations of the street medicine model to meet their patients "where they are at," improve their social determinants of health, and enhance the health and well-being of this underserved and medically vulnerable population. Participants overwhelmingly perceived street medicine to be an acceptable model for service delivery with unhoused populations and advocated for its expansion.

Conclusion & Discussion: This study highlights both the promise and the challenges of providing healthcare to unhoused populations through the street medicine model. While participants possessed a positive affective attitude about and belief in the ethicality of street medicine services, participants also discussed the obstacles to service provision, including the lack of supportive infrastructure, such as case management, behavioral health services, and access to housing resources. These findings suggest that while street medicine is a valuable approach to addressing the immediate healthcare needs of unhoused individuals, its effectiveness hinges on addressing systemic barriers such as access to housing and comprehensive social support services. As such, expanding the street medicine model requires not only enhancing the capacity for healthcare delivery in nontraditional settings but also fostering greater collaboration between healthcare providers, social services, and community organizations to address the broader social determinants of health among the unhoused population. Given its potential to improve the health and well-being of this medically vulnerable population, further investment and policy support for the expansion of street medicine programs are strongly warranted.

References: Kaufman, R. A., Mallick, M., Louis, J. T., Williams, M., & Oriol, N. (2024). The Role of Street Medicine and Mobile Clinics for Persons Experiencing Homelessness: A Scoping Review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 21(6), 760.

National Alliance to End Homelessness. Racial Disparities in Homelessness Persist: A Data Snapshot. https://www.endhomelessness.org/resource/racial-disparities-in-homelessness-persist-a-data-snapshot/. Accessed 10 July 2024.

Omerov, P., Craftman, Å. G., Mattsson, E., & Klarare, A. (2019). Homeless persons’ Experiences of Health‐ and Social care: a Systematic Integrative Review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(1).

Richards, J., & Kuhn, R. (2022). Unsheltered Homelessness and Health: A Literature Review. AJPM focus, 2(1), 100043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.focus.2022.100043

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2023). HUD 2023 PIT Count Report. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2023-AHAR-Part-1.pdf.

Tito E. (2023). Street Medicine: Barrier Considerations for Healthcare Providers in the U.S. Cureus, 15(5), e38761.

Learning Objectives:

- Describe street medicine team members' perceived effectiveness and self-efficacy in providing street medicine services to unhoused populations.

- Identify rapport building strategies to enhance engagement and continuity of care among unhoused populations.

- List common limitations to providing street medicine services to unhoused populations.